“Our Shared Transportation Future” with General Darren W. McDew

Movement equals action, to paraphrase Albert Einstein. That’s true in science. It’s true in business. It’s true in health care, education, media—in every facet of the American patchwork.

And it’s true in the U.S. military, where humanitarian and combat missions rely on swift transportation solutions where success or failure can mean lives saved, or lives lost.

“We can bring an immediate force tonight anywhere on the planet,” said General Darren W. McDew, commander of the U.S. Transportation Command (USTRANSCOM), who spoke recently at Volpe. “Not many nations can do that. Then there’s that decisive force—and when we need that force, we can bring that, too.”

Watch video highlights of General Darren W. McDew's talk at Volpe, “Our Shared Transportation Future.”

How Transportation Underpins Military Success

USTRANSCOM delivers global defense logistics anyplace, anytime, and for however long is needed. It is one of nine central unified combatant commands that direct U.S. military priorities around the world.

Late last year after Hurricane Matthew hit Haiti, the U.S. Southern Command convened a task force of 27 people to lead humanitarian efforts—24 of those people were from USTRANSCOM, McDew said.

From 2013 to 2016 during the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, USTRANSCOM supplied equipment and pilots to evacuate patients and provide humanitarian aid, medical supplies, and portable hospitals.

And last month, when two B-2 bombers hit ISIS training camps in Libya, more than a dozen KC-135 Stratotankers deployed by USTRANSCOM refueled the bombers.

The KC-135A refueling aircraft was one of the first models McDew learned to fly.

“We underpin everything there is about the United States military,” McDew said. “The army transporters say it best. They say, ‘Nothing happens until something moves.’”

New Challenges

McDew discussed several challenges to the nation’s safety and security that are either here today or coming soon.

The first challenge is new potential adversaries that can match the U.S. military in manpower and technological advancement.

“We have enjoyed dominance in every domain for as long as I can remember,” McDew said. “We haven’t been challenged probably since World War II in any one domain. But we’re facing an adversary in the future that can bring problems to bear in every domain.”

Even without manpower and advanced technologies, an adversary that can execute cyberattacks may be enough to do serious damage, McDew said. Those attacks don’t always require sophisticated software or hacking know-how. Because USTRANSCOM and other military commands contract with private businesses, an adversary could theoretically target a private business contracting with the government and tunnel backwards to obtain government information.

Finally, there is a workforce problem in the public and private sectors that is not trending in the right direction: there simply aren’t enough pilots, mariners, and truckers, McDew said.

“We’ve got a national problem with inventory of people willing to do these jobs,” McDew said. “Autonomy may be a solution set, but that’s not today. We’ve got a problem brewing today.”

Requiring New Thinking

When McDew climbed into the cockpit of the KC-135 for the first time as a young pilot, he settled in and put on his headset. His instructor told him to uncover his left ear. The instructor uncovered his right ear.

McDew wondered why.

It turned out that the radios in that early model of the KC-135 were loud and did not transmit well. For two people in the same cockpit, it made more sense to yell at each other than to use the radio.

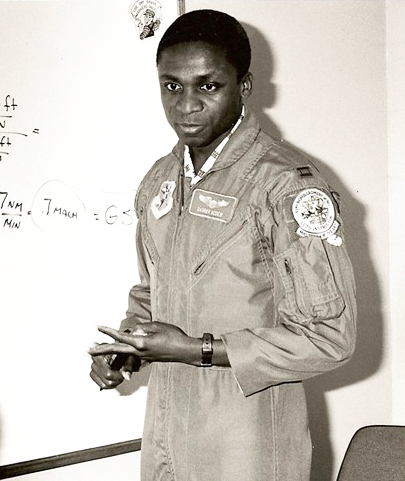

General McDew more than 30 years ago instructing students on piloting the KC-135A refueling aircraft.

Twenty years later, McDew had flown all kinds of airplanes. The C-141, the C-17, the C-130, the C-9, the C-21, the Gulfstream. He didn’t have to remove one side of his headset in any of those models because of improved technology. Then he got back into a KC-135—a newer version—and he didn’t remove one side of his headset.

His instructor noticed. He told McDew they still did that in the KC-135. But like all modern airplanes, the newer KC-135 had something called a hot mic, which is voice activated and transmits audio clearly.

McDew had switched on the hot mic. But the instructor wasn’t using it, and had never used it. And he couldn’t explain to McDew why he removed one side of his headset, other than that’s how he’d been taught, and so that’s what he taught his students.

“When I tell that story, people think I’m talking about radios,” McDew said. “I’m talking about habits you bring forward and you teach or demand of others to do that don’t add the value they once did. And you perpetuate it. You know the worst carrier of that? Success. You must force yourself, the more successful you’ve been, to be different.”