Transportation Drives Economic Competitiveness in Megaregions

From globalization to technological advances, the more complex our world becomes the more interconnected we are in trade, communication, and transportation.

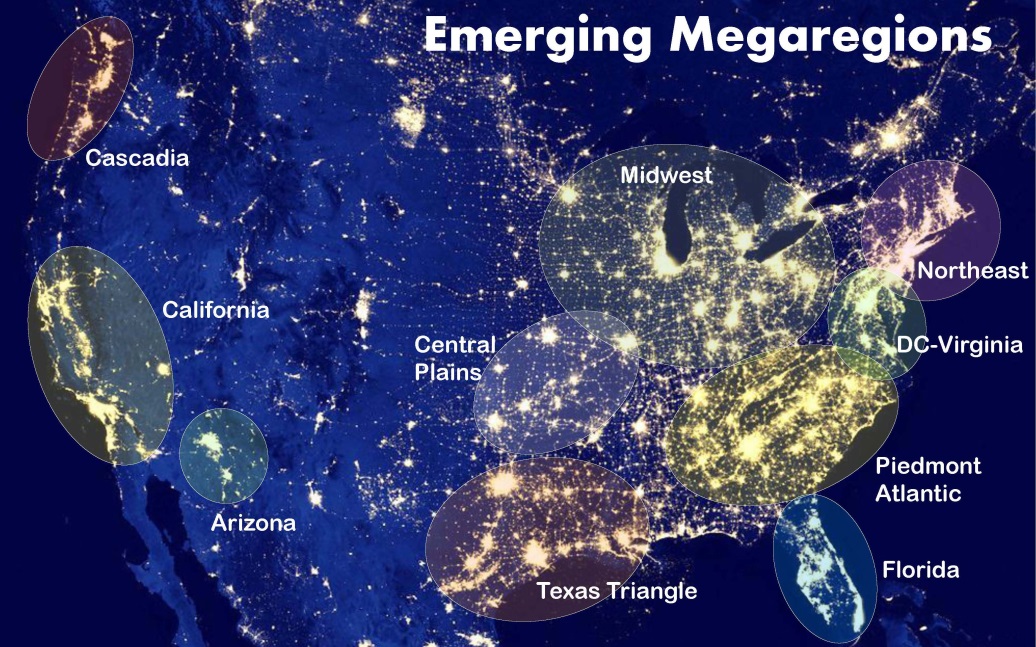

In America our urban centers are trending toward megaregions—collections of large cities, suburbs, exurbs, and the areas between requiring extensive, linked transportation networks.

“Cities anchor megaregions,” said Dr. Catherine Ross, director of the Center for Quality Growth and Regional Development at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and the second presenter in Volpe’s Transportation and the Economy speaker series. “Cities are not new. They’ve been around for a very long while. But they are connected now. They are operating economically in a fundamentally different way.”

Why Megaregions Matter

America’s metropolitan areas, with 150,000 to 10 million people, account for 70 percent of our gross domestic product. Many of these areas are part of the 10 megaregions that demographers have identified along the coasts and through the South and Midwest. More than 90 percent of Fortune 500 companies are headquartered in megaregions, and more than three-quarters of national employment takes place in megaregions, Dr. Ross said.

“Not all corridors are equal,” she said. “Some are directly tied to global markets and our economic viability. Do we conceptualize them in that way? If these corridors don’t work, then we don’t work.”

Transportation Planning for Megaregions

There are two critical truths about megaregions. The first is that they do not respect geopolitical boundaries. The second is that they play different roles across the national and global economic landscape.

“What I care about is not a traditional map, but a conceptual map that looks at places critical to our economy and asks how transportation does or does not support them,” Dr. Ross said.

The Northeast, California, and Texas Triangle megaregions thrive on technology, international trade, and goods that are shipped to the rest of America. The Central Plains region is projected to produce nearly half a trillion dollars in commodities by 2035, while most goods produced in the Piedmont and Cascadia regions remain in-region.

Each region has dozens of local transportation agencies. The Midwest, Northeast, and Piedmont megaregions have a high number of states and relatively more transportation agencies, which may make it challenging to do collaborative planning. Cross-collaboration and a deep understanding of the needs unique to each megaregion can help planners prioritize transportation projects so that America’s megaregions remain economically strong.

Moving Forward with Megaregions

If megaregions indeed represent the way that transportation planners think about their work in the future, several challenges need to be recognized today, Dr. Ross said. The existing highway network may not support employment trends—for example, highways that serve Atlanta, in the Piedmont region, are already chronically congested. Planning for megaregions can also have a significant negative or positive impact on carbon emissions.

But there are also clear paths forward.

“The rail network offers the capacity to accommodate our freight needs,” Dr. Ross said. “About 45 percent of our rail network will still be under capacity by 2035. As I’ve suggested, in many parts of the United States, particularly in the Southeast, we are pipeline poor and we don’t move very many of our commodities by rail.”

Megaregions are just one way for planners to conceptualize how goods, people, and ideas move regionally and across America. The last piece of the megaregion puzzle is financing. Funding policies for megaregion planning should match a holistic megaregion planning approach, by taking environmental concerns into account and removing limitations set by state boundaries, Dr. Ross said. It’s an interconnected world, after all.